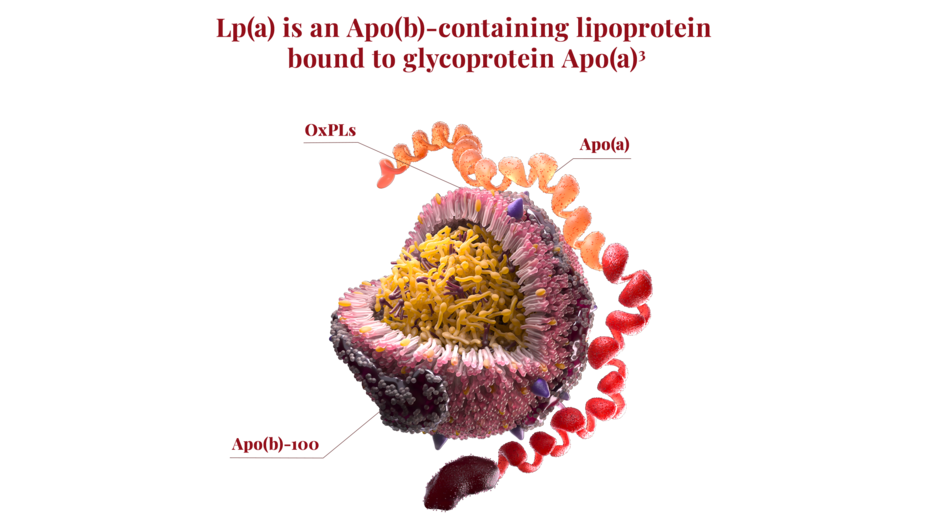

What is Lp(a)?

Lp(a) is a unique lipoprotein that may play a role in hemostasis, help promote tissue repair, and wound healing2

Lp(a) is prothrombotic, proinflammatory, and ~6-fold more atherogenic than LDL-C per particle basis3-5†‡

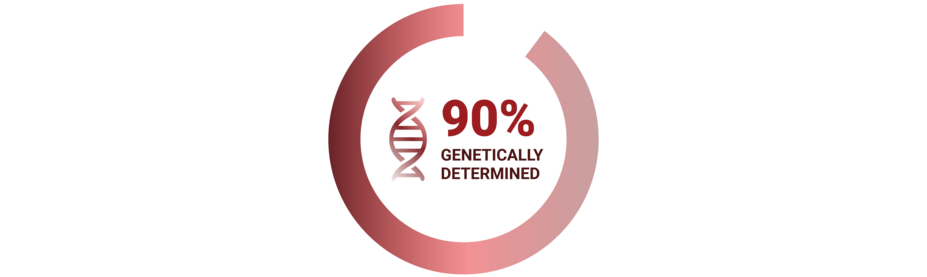

Figure: Lp(a) levels are ~90% determined by genetics. Lp(a) concentrations have been found to be inversely related to the number of copies in the kringle IV type 2 (KIV-2) domain of Apo(a).6

*Retrospective cohort study of patients with ASCVD and an Lp(a) level (N=11,310) using US electronic medical records from January 2014-June 2023. Of those with premature ASCVD (n=2684), 29.7% had elevated Lp(a). Premature ASCVD was defined as MI, IS, or a PAD-related diagnosis/procedure before age 55 in males or 65 in females on or after first ASCVD diagnosis. Due to inherent limitations of EMR data and a predominately Caucasian cohort, findings should be cautiously interpreted and may lack generalizability.1

†Clinical relevance is unknown.

‡Atherogenicity was defined as the difference in CHD risk per unit difference in Lp(a) or LDL particle number (molar concentration). This study was based on the UK Biobank population (>502,000 UK residents) who were predominately of European ancestry. The generalizability of the findings was tested in a replication cohort: the CARDIoGRAMplusC4D (Coronary ARtery DIsease Genome wide Replication and Meta-analysis [CARDIoGRAM] plus The Coronary Artery Disease Genetics) data set. Study did not differentiate between subjects with or without CHD at baseline. Analysis focused on the ApoB component of Lp(a).5

Lp(a) levels are ~90% genetically determined3,7

Elevated Lp(a) levels are defined as ≥50 mg/dL or ≥125 nmol/L8

~1 in 5 people worldwide may have elevated Lp(a)4,9

Elevated Lp(a) has emerged as one of the strongest single genetic drivers of CAD7,10

Higher Lp(a) levels are associated with a greater risk for MI11

The risk for CV events from elevated Lp(a) is lifelong and cumulative over time12

Lp(a) levels are typically established by 5 years of age and remain relatively consistent over time12,13

Lp(a) levels are generally not impacted by diet or lifestyle7,12,13

Risk for a CV event from elevated Lp(a) is cumulative over time12

Elevated Lp(a) can increase risk for CV events12

Elevated Lp(a) can increase risk for peripheral artery disease, CAD, MI, and stroke10,12

Baseline risk for a lifetime major CV event increases with increasing Lp(a) levels12

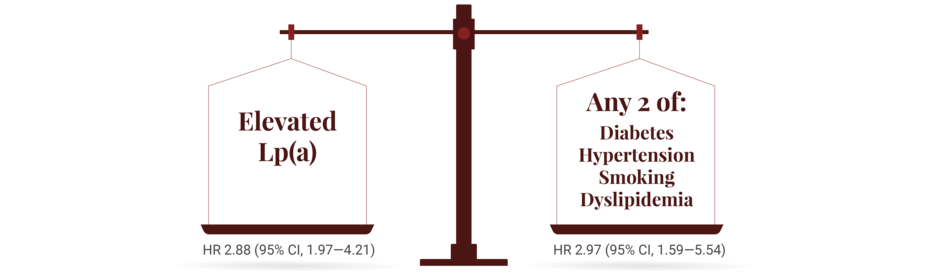

In one retrospective cohort study of patients who did not have prior ASCVD, the increased risk from elevated Lp(a) for a first acute myocardial infarction (MI) was shown to be similar to having 2 standard modifiable risk factors14§

Elevated Lp(a) is an independent driver of CV risk3,8,16,17

The risk from elevated Lp(a) is independent of other CV risk factors3,8,16,17

Patients with elevated Lp(a) who have had a CV event are at increased risk for a recurrence15,16,18,19

The absolute risk of major adverse CV events in patients with CVD has been found to increase with increasing levels of Lp(a)16||

||Based on a prospective cohort study of white adults of Danish descent with CVD from the Copenhagen General Population Study (N=2527). Major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) was defined as CV death, nonfatal MI, coronary artery bypass graft, percutaneous coronary intervention, and stroke. Those with Lp(a) <10 mg/dL (<18 nmol/L), 10 to 49 mg/dL (18–104 nmol/L), 50 to 99 mg/dL (105–213 nmol/L), and ≥100 mg/dL (≥214 nmol/L) had incidence rates of 29 (95% CI, 25–34), 35 (30–41), 42 (34–51), and 54 (42–70) per 1000 person years for MACE, respectively. Generalizability of results to other ethnicities is limited.16

Some people may have higher Lp(a) levels than others

For people of African ancestry20,21:

Median Lp(a) levels were shown to be higher when compared with other racial subgroups

For people of South Asian ancestry22,23:

Some studies have shown median Lp(a) levels were second highest after those of African ancestry

Professional organizations are recognizing the emerging importance of Lp(a) testing in CV risk assessment and stratification.8,24-26

References: 1. Byrne H, Sinha S, Pradhan H, et al. How common is elevated Lp(a) in premature ASCVD patients? A real-world study using a large US electronic health record database. Poster presented at: European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) Congress; May 4-7, 2025; Glasgow, UK. 2. Vinci P, Di Girolamo FG, Panizon E, et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(18):6721. 3. Reyes-Soffer G, Ginsburg H, Berglund L, et al. Lipoprotein(a): a genetically determined, causal, and prevalent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42(1):e48-e60. 4. Tsimikas S, Fazio S, Ferdinand K, et al. NHLBI Working Group recommendations to reduce lipoprotein(a)-mediated risk of cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(2):177-192. 5. Björnson E, Adiels M, Taskinen MR, et al. Lipoprotein(a) is markedly more atherogenic than LDL: an apolipoprotein B-based genetic analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83(3):385-395. 6. Schmidt K, Noureen A, Kronenberg F, Utermann G. Structure, function, and genetics of lipoprotein (a). J Lipid Res. 2016;57(8):1339-1359. 7. Tsimikas S. A test in context: lipoprotein(a): diagnosis, prognosis, controversies, and emerging therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(6):692-711. 8. Koschinsky ML, Bajaj A, Boffa MB, et al. A focused update to the 2019 NLA scientific statement on use of lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice. J Clin Lipidol. 2024;18(3):e308-e319. 9. US Census Bureau. Current Population. 10. Clarke R, Peden J, Hopewell J, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2518-2528. 11. Kamstrup PR, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Steffensen R, et al. Genetically elevated lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2009;301(22):2331-2339. 12. Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG, et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: a European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(39):3925-3946. 13. Wilson DP, Jacobson TA, Jones PH, et al. Use of Lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice: a biomarker whose time has come. A scientific statement from the National Lipid Association. J Clin Lipidol. 2019;13(3):374-392. 14. Shiyovich A, Berman AN, Besser SA, et al. Association of lipoprotein (a) and standard modifiable cardiovascular risk factors with incident myocardial infarction: the Mass General Brigham Lp(a) Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024 May 21;13(10):e034493. 15. Berman AN, Biery DW, Besser SA, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with or without baseline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83(9):873-886. 16. Madsen CM, Kamstrup PR, Langsted A, et al. Lipoprotein(a)-lowering by 50 mg/dL (105 nmol/L) may be needed to reduce cardiovascular disease 20% in secondary prevention. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:255-266. 17. Willeit P, Ridker PM, Nestel PJ, et al. Baseline and on-statin treatment lipoprotein(a) levels for prediction of cardiovascular events: individual patient-data meta-analysis of statin outcome trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1311-1320. 18. MacDougall DE, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Knowles JW, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and recurrent atherosclerotic cardiovascular events: the US Family Heart Database. Eur Heart J. Published online May 7, 2025. 19. Welsh P, Zabiby AA, Byrne H, et al. Elevated lipoprotein(a) increases risk of subsequent major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and coronary revascularisation in incident ASCVD patients: a cohort study from the UK Biobank. Atherosclerosis. 2024;389:1-8. 20. Guan W, Cao J, Steffen BT, et al. Race is a key variable in assigning lipoprotein(a) cutoff values for coronary heart disease risk assessment: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(4):996-1001. 21. Paré G, Çaku A, McQueen M, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels and the risk of myocardial infarction among 7 ethnic groups. Circulation. 2019;139(12):1472-1482. 22. Makshood M, Joshi PH, Kanaya AM, et al. Lipoprotein (a) and aortic valve calcium in South Asians compared to other race/ethnic groups. Atherosclerosis. 2020;313:14-19 23. Patel AP, Wang (汪敏先) M, Pirruccello JP, et al. Lp(a) (lipoprotein[a]) concentrations and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: new insights from a large national biobank. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:465-474. 24. Writing Committee, Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, et al. 2022 ACC Expert consensus decision pathway on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(14):1366-1418. 25. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1082-e1143. 26. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646.